A major Airbnb showdown is delayed (until tonight) as new information emerges that the industry is gobbling up more housing than before and the river remains a major battleground in the city’s future

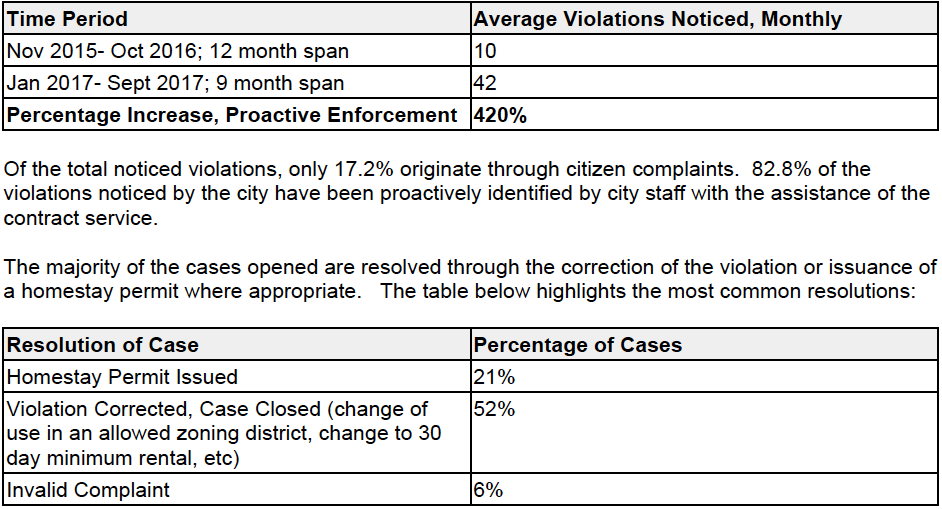

Above: a key part of the Oct. 24 presentation on the city’s enforcement efforts against illegal Airbnb-style rentals.

The Oct. 24 Asheville City Council meeting was supposed to be a showdown. This summer, on a 4-3 vote, the elected officials sent a proposed rezoning of the River Arts District back to the city’s planning commission, insisting that it include a ban on renting out whole homes and apartments as Airbnb-style rentals for tourists.

That issue, to put it mildly, has remained a contentious one. The impact of the short-term rental industry in Asheville is massive, far larger than other major N.C. cities combined. Some stumping for the industry, usually multiple property owners participating in it, have pushed Council to ease the rules, claiming they have the same rights as hoteliers to make big profits off the tourism boom.

But while some cash-strapped local property owners do rent out rooms in homes they live in, whole homes and apartments are a much hotter commodity. Media investigations, including by the Blade have accordingly shown that the industry favors larger companies and owners of multiple properties who are poised to reap the profits from a tourism boom and one of the harshest housing markets in the Southeast.

This has fueled a backlash, as critics to contend that the industry has worsened an already-dire housing crisis and that the push to relax short-term rental rules is largely just about making the rich richer and kicking locals (over half the city are renters) out of their homes to do so while turning residential neighborhoods into party destinations.

In 2015 Council opted for a two-pronged approach. Whole home/apartment Airbnbs, dubbed “short-term rentals” in planning jargon and already banned in much of the city, received harsher fines and stricter enforcement but the city eased restrictions on “homestays,” rooms rented out by a resident who lives in the same dwelling. Those profiting from the industry have kept pushing for the rules to be relaxed in one area or another while critics said that enforcement remains too lax and the short-term rentals are still legal — and pushing locals out — in too many places.

Lately the critics have had some success. Council member Cecil Bothwell, one of the industry’s staunchest allies, lost his re-election bid in the primary. The candidates who made it through tended to be in favor of scaling the industry back in some major ways by, for example, prohibiting whole home/apartment Airbnbs where they’re currently allowed in places like downtown or, well, the RAD. In early October, Council unanimously decided not to allow whole home/apartment short-term rentals in a swath of Haywood Road and consider extending the ban along the entire corridor.

With the RAD rules set for another vote, the room was packed and events looked to be lining up for a major political showdown on Oct. 24.

It didn’t happen.

Arriving after the meeting’s start, Mayor Esther Manheimer revealed that due to a “challenge to my ability to vote on the River Arts District” zoning and needed to consult with the N.C. State Bar. The nature of the challenge was undisclosed, though Manheimer works as an attorney for the prominent Van Winkle law firm and that’s led to her having to recuse herself from some development matters in the past. At her request, Council agreed to delay the RAD zoning vote to tonight’s meeting (according to an Asheville Citizen-Times report, Manheimer plans to vote this evening).

But things didn’t end there.

Short-term diagnosis

Also on the agenda was a report on how the city’s enforcement of its short-term rental rules was actually going. After the city stepped up enforcement in 2015, it also ramped up its effoets last year, hiring outside help to find violators

Bizarrely, the report itself wasn’t presented to Council, instead being contained in the online agenda packet. While Council occasionally has minor reports designated online-only, doing so on such a major and contentious issue is unheard of.

The report noted that enforcement had ramped up, from 10 citations a month during the first year of increased in enforcement to an average of 42 per month now (at one point the number rose as high as 72 per month). It also revealed that there are 548 legal homestay permits, though about half of these are private rooms and suites that the city claims are advertised as “whole home/apt” online. At the same time, the report note that making sure homestay permits weren’t just being used as a cover to rent out whole homes and apartments remained a major issue. Indeed, it found the following major concerns:

• The number of unidentified units evading detection and continuing to operate illegally.

• False representation of residency, web postings, and leases with homestay permits along with the accurate identification of livable space and unit separation .

• Property owners seeking to operate homestays from detached structures.

• In commercial districts, an increase in the number of residential dwelling unit conversions to short-term lodging.

• In commercial districts, a significant increase in the number of new residential projects being constructed for the purpose of providing lodging.

Council member Gordon Smith, one of the staunchest foes of the industry’s expansion, noted that it looked like enforcement efforts were having an impact but that he was still concerned about how to “get to zero” illegal short-term rentals.

“Does this amount of staffing get us where we need to go or do we need more?” Smith said. “Or do something else entirely.”

Head planner Shannon Tuch claimed that the city’s enforcement efforts tended to work once they found an illegal Airbnb but “there are quite a number that are still unidentified.”

Smith asked how that could be remedied.

“I’m not sure, we’ve scratched our heads on that,” Tuch replied. “Honestly, we’re really quite proactive and ahead of a lot of other cities in this realm.”

Vice Mayor Gwen Wisler and Council member Julie Mayfield inquired further about the methods the city uses to find illegal short-term rentals, and Tuch replied that the service her department uses monitors online sites. Mayfield wondered if direct city investigations of the properties in question couldn’t also work.

Smith noted he’d seen owners of illegal short-term rentals “go to great lengths” to keep their properties off the radar.

Council member Keith Young asked if the efforts were making a dent.

“We’re always dealing with a new supply,” Tuch said. “We know that the number of rentals seems to hover in the 900-1000 range, the number of notices of violation have dropped down some and that might be us starting to get to the point we’re maintaining. The properties that can be legal are becoming legal.”

Young then compared the Airbnb enforcement efforts directed at property owners to “the war on drugs, it’s give and take.”

Smith claimed the homestay program was an effort to allow some locals to make money off the tourist influx “without jeopardizing the housing stock.” He then turned to asking how much of an impact legal short-term rentals in areas like the RAD and downtown were having on the issue.

Property owners are required to formally notify the city when they switch residential or other units over to lodging and Assistant City manager Cathy Ball said they could analyze what information they had. Wisler pushed to know more, especially about newer rentals.

“We’re hearing that a lot, out in the community, that there are commercial properties flipping into short-term rentals,” she said. “Even though it may not have been housing use before, now people are converting small businesses into short-term rentals.”

Smith and Mayfield agreed.

But Tuch admitted that “the permit system we use has some limitations” and despite the city having documents of the units that had become whole home/apartment short-term rentals, it would be incredibly difficult to actually find them all due to the state of the city’s records.

“We’ve tried some trials, we’ve not felt confident about the data we’ve collected.” They would, she added, try to get the data nonetheless.

“Even if data isn’t complete, we can’t use that as an excuse not to start looking at it,” Wisler said. “This [expansion of STRs in commercial areas] isn’t good, if that’s what we’re seeing, we need to address it whether we have perfect, accurate numbers or not. Citizens sense that what you’re saying is happening and it’s happening rapidly. Council can’t take a pass because we don’t have all the data in place.”

“I don’t mean to suggest we won’t come back with some data,” Tuch said. “It may take some time.”

“Very soon, in my perspective, once it happens its very hard to take away,” Wisler replied.

Mayfield asked Tuch to clarify that apartment and condo developments in downtown were now seeking to become short-term rentals for tourists instead, “that same building will now exclusively be short-term rentals rather than lodging for people who live here.”

“Exclusively or in combination,” Tuch answered. “Especially in downtown they’re coming in and converting.”

“We’re also seeing multi-family structures coming in and permitting as short-term rentals,” she added.

That fact appeared to shock some Council members.

“That’s incredibly distressing,” Mayfield said.

“It’s quite possible a lot of people who would by a condo in Asheville are just going to stay here during the summer and then go back to Florida,” Bothwell said. “They’re not going to rent it long-term, so why shouldn’t they be able to rent it short-term while they’re gone.”

Manheimer asked staff to look for ways to “double down” on enforcement on illegal short-term rentals and wanted “to get a handle on how many units we’re talking about.”

“There are definitely coastal communities where this is the way it’s done, people just finance vacation rentals,” “We’re having a discussion now if that’s the kind of community we want to be or if we want to continue to be a place for long-term residents.”

She noted the same fight was going on in other tourist destinations, cities “great cities that are slightly being squeeze by their greatness.”

That diagnosis certainly upped the stakes for Council’s decision tonight, as did a vote that happened in the same meeting, when Council approved a hotel in the RAD despite no commitment to supporting local businesses or paying a living wage (Smith and Wisler voted against the approval). The area around the river, marked by de facto segregation, the legacy of redlining and rapid gentrification, remains a key focus of Asheville’s fights over what kind of city we will be and whom our power structures will work for.

In addition to Airbnb and its zoning rules, tonight Council’s also set to consider a 133-unit apartment complex that offers no affordable units at all. This fight’s going nowhere.

—

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by our readers. If you like what we do, donate directly to us on Patreon or make a one-time gift to support our work. Questions? Comments? Email us.