As public pressure to fight a state-imposed racist gerrymander mounts, Council finally breaks their silence, revealing more delays and refusing to challenge a part of the law giving them another year in office

Above: Mayor Esther Manheimer, who finally responded to mounting public outcry about the city’s delay in battling a state-imposed gerrymandered system for local elections. File photo by Max Cooper.

For months two questions have loomed over Asheville politics: would there be an election this year and would it use districts imposed by the GOP-dominated general assembly, ones clearly targeted at breaking up and reducing the power of the black vote?

That was due to a state law, passed last summer, that forced a system of five districts on Ashevile, and delayed elections by a year (normally three Council seats would be up for election in 2019). Other local governments that faced similar laws had quickly fought them in court, and won. But over the past six months, Asheville’s government stayed silent, despite 75 percent of city voters in a 2017 referendum declaring their opposition to a legislature-imposed gerrymander. But in phone calls, emails, social media posts and, finally, in comments before Council itself, locals started to push back, wondering why City Hall wasn’t fighting the Republican-drawn plans.

Due to that public pressure, on Jan. 22 locals finally got some answers to those two key questions. Will there be an election this year? Not if Council can help it (giving them essentially another year in office the voters didn’t give them) Will they fight the district system? Maybe, some day, after more legal counsel.

While the calls from members of the public — and Council’s responses — took place in the course of less than 15 minutes at the end of the three hour meeting, given the massive public opposition to the new state system they promise to be the beginning of a much larger political battle.

Divide and conquer

Currently, Asheville’s city elections run on what’s called an “at-large” system. The six Council members and the mayor are all elected citywide, and every city voter can vote for all of the open seats. Terms are staggered so three Council seats are up for election every two years. The last election (which included three Council seats and the mayor’s race) was in 2017. The next election is supposed to be this year.

The question of who district or at-large systems favor is a complicated one, and can vary from area to area. In the case of Asheville, where historically black neighborhoods like Shiloh, Southside and Burton Street are in different parts of the city, an at-large system can be friendlier to more organized black voting power. If black communities throughout the city see given candidates as appealing to their goals and interests, they have a better chance of getting them in office, and they can vote for candidates in every seat regardless of where in the city they live.

Indeed, that’s what’s happened in the past two election cycles. Going into the 2015 elections Asheville had an all-white Council. By the end of 2017 there were two black Council members, the most in three decades. The district systems repeatedly proposed by Republicans and their allies have, not surprisingly, sought to split that vote apart.

While the local far-right and conservative legislators had long discussed imposing a district system on Asheville, the idea got far more momentum after local conservatives were demolished in the 2015 local elections (three experienced right-wing candidates failed to make it past the primary). The following year, Republican state Sen. Tom Apodaca (whose district includes a sliver of South Asheville), tried to force through a particularly harsh bill carving the city up into districts, but failed when the state House actually rejected the measure.

The next year, Apodaca’s successor — Sen. Chuck Edwards — took up the measure again. His bill directed the city to draw up a system with six districts, with criteria that would inevitably involve breaking up precincts with larger numbers of black voters and impose one of the strictest district systems in the state (most cities that have district systems have a mix of at-large and district seats). This time, over the opposition of Democratic legislators, it passed the state legislature.

Council refused to implement it, and put Edwards’ plan to city voters in a referendum that year. They rejected it overwhelmingly, with 75 percent of ballots cast going against the GOP plan.

So last year, Edwards proposed another bill, still splitting up black voting power (and accordingly condemned by both of Asheville’s black Council members), but drawing five districts instead of six (leaving one Council member and the mayor elected at-large). This time, something surprising happened.

Rather than opposing the GOP gerrymandering plan, Democratic Sen. Terry Van Duyn broke with her colleagues (every local state representative publicly opposed the measure) and supported it after Edwards agreed to delay city elections for a year (meaning the next city elections would take place in 2020 and 2022), which he readily did. Neither Asheville’s voters or Council had sought that change.

‘We don’t want it’

Asheville isn’t the first local government to face such a gerrymandering plan. Both Wake County and Greensboro were also targeted by similar legislation. In those cases, they quickly challenged the new state laws in court, and won. The Wake gerrymander was thrown out in 2016, Greensboro‘s the following year.

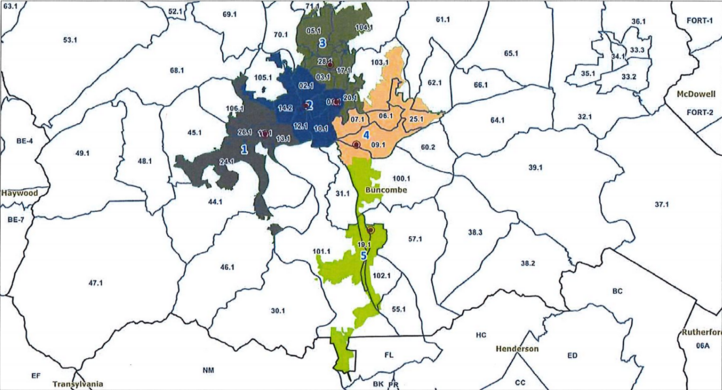

Asheville election districts passed by the GOP-dominated state legislature in 2017, splitting up voting precincts with larger numbers of black voters

But while Asheville’s elected officials had publicly opposed the GOP gerrymander of their own elections, in the month after the new bill passed, they stayed strangely silent. Late last year, the Blade asked them what was going on. Mayor Esther Manheimer said the city was still considering whether to fight and Council member Julie Mayfield said they might wait until a new city attorney had been appointed, which could take well into the Spring.

Locals weren’t willing to wait that long, and as the issue gained more public attention, more of them started to ask publicly why Council wasn’t fighting the matter. Two locals urged them to do so at the Jan. 8 Council meeting. On Jan. 22, more joined that fight, speaking during the open public comment period at the end of the meeting.

“I saw the proclamation recognized the city’s role in racial trauma,” Matilda Bliss said, referring to a proclamation at the meeting’s beginning recognizing Jan. 22 as a Day of Racial Healing and noting local government’s history of not heeding referendums that pressed them to act in an anti-racist direction.

“Overwhelming numbers of Ashevillians voted against these districts,” Bliss said. “We don’t want it. And yet, that was a while ago. Why are we still not filing action on this? Is it because there’s something we’re not aware of? Is it because there’s a shift that’s intentionally being put into place to deny the public’s wishes on this?”

“The clock is ticking, Council must act now to file these motions,” she continued. “If we wait until we have another city attorney it will be too late” to have an election this year.

“I’m back again to urge you, as strenuously as possible, to fight the senate bill districting Asheville’s elections,” Casey Campfield said. “We’re nearing February and we still don’t know if we’re having elections this year. The assumption is that we’re not, but if you act, you can do something about this. These kind of laws have been overturned in other cities.”

“Most of you have expressed dissent with this law. Seventy percent of Asheville’s voters — I’ve never witnessed a referendum that had such a strong turnout in one direction — do not want these districts,” Campfield continued. “We do not want the state government, particularly this current state government, drawing districts in Asheville. They’re not necessary, there’s nothing wrong with our current system. We haven’t heard anything from you about this and we need to know what’s happening, we need to know where you stand.”

“I call on you to think about what the districting of Asheville will mean not just for Asheville right now but for Asheville in the future,” Kim Roney, a member of the city’s transit board and a former Council candidate, said. She tied the fight against districting to the larger struggle for civil rights. Council needed to “unite Asheville around our shared needs and to do something to fight the districting of Asheville.”

Those calls clearly had an effect. After months of relative silence, some on Council finally spoke about the districting issue.

“We have asked the interim city attorney to go ahead and solicit some legal advice for us,” Manheimer said. She noted interim City attorney Sabrina Rockoff “is not an expert in election law, it’s sort of a specialty area. But there are some attorneys in this state who are experts and we’ve asked her to reach out to some to advise us about what our options are.”

Manheimer noted that the bill did not take away Asheville’s right to modify its own election system via referendum, as previous bills have. She claimed that the lack of referendum was the key reason the Greensboro bill was struck down. “One question: is that option open rather than a lawsuit, if it is is that a better option: how do you do that? When does it happen?” There were also the strengths and weaknesses of potential legal claims to consider, she noted, as “we’re in an unprecedented situation.”

But Manheimer left some key information out in this summation. While the Greensboro gerrymander was partly rejected because it took away voters’ right to a referendum, a federal judge also tossed it out because she found that one district was specifically racially gerrymandered and others were drawn to weaken Democratic voting strength. The Wake County case revolved around issues of equal representation, not the denial of a referendum.

“We really need some expert advice to make a decision before we go forward,” Manheimer concluded.

But the part of the law delaying Asheville’s elections by a year was not part of a change to the city charter, Manheimer said, so there’d been no consideration of a potential legal challenge, “because it wasn’t a change to our charter, unlike the districts.” Council, she claimed, planned to let it stand.

If this part of the law remained intact, it would give all Council members and the mayor another year in office that the voters didn’t give them.

Lawsuits can be filed against parts of a state election law regardless of whether they’re part of a city charter or not.

Manheimer then, however said that “I did support, and I do support” the move to even-year elections. She said she had spoken with Edwards “many times” about a possible districting bill. While she had advocated against the move in those conversations, she claimed she told the state senator that “if you are going to do this, which I don’t think you should, I asked him to move the elections to an even year, because in my opinion, it would help with voter turnout.” Van Duyn was, Manheimer said, “acting at least on my behalf in that request.”

Interviewed by the Blade at the time, however, Manheimer gave a somewhat different account of how the law had proceeded:

But the amendment [Van Duyn] was seeking didn’t have any prior support from Council or the public and, indeed, they weren’t even given an opportunity to discuss it. Manheimer told the Blade that while she personally likes the idea of moving city elections to even years and had discussed the idea with Van Duyn briefly, no Council member had sought the change or taken a position on the issue.

Manheimer adds that given the rest of the district bill “it’s still putting lipstick on a pig.”

Backing up Manheimer, Mayfield then noted that former City attorney Robin Currin had given Council a closed session briefing on the district election issue in her last closed session before leaving to take a job in Raleigh, and “she was very clear in saying…”

“I don’t think you want to disclose legal advice and waive privilege,” Rockoff then said, cutting off Mayfield from proceeding further. Manheimer said Council would have more for the public when they figured out a way to talk about it.

If, as Mayfield seemed about to imply, Currin had advised Council against fighting most or some of the state gerrymander and election delay, that’s not particularly surprising. Currin was known for far-right legal views about the role of local government, and on issues from trans rights to housing to racial equity, repeatedly advised Council to take a more conservative stance, sometimes even telling them they couldn’t enact measures other local governments in N.C. had.

Mayfield then revealed that the city had failed to find a replacement for Currin (Council and senior staff had sought a new city attorney in a secretive process over the past few months).

But while Council adjourned with no further discussion that evening, it’s doubtful the issue is going away. Public conversations about it have only increased in the days since.

Fight or flee

As a longtime observer of City Hall, I have to say that the explanations offered by Council for the delays are particularly strange. Even an expensive legal battle might cost, at most, several hundred thousand dollars. While that’s a lot of money the city’s budget is over $180 million, so it has significant resources to hire or cooperate with outside attorneys — including those with significant voting rights experience — if it chose to. And “chose” is the operative word, because increasingly what we’re hearing from locals is that they don’t believe Council wants to fight this at all.

There could be a number of reasons for that. The battles between centrists and more left-leaning voters and candidates are currently the defining dynamic of city politics. Increasingly organized black voting power has brought issues of de facto segregation to the forefront of our city’s politics, in ways that are deeply uncomfortable for the “progressive” status quo and have shaken up their assumptions about the way local elections work in this town.

Given that, it’s not impossible to see some Council members thinking that shifting the election system in a more conservative (and whiter) direction might help them hold onto power. The state-imposed system would also change things outside of political campaigns. A system rigged in a more right-wing direction would be a lot less responsive to public pressure from Asheville’s fairly left-leaning population. Such a local government would be far less supportive of measures like last year’s NAACP-backed policing reforms, and even more likely to pursue moves like trying to shut down left-wing organizing spaces and needle exchanges.

Some of them might just want another year in office. If that’s not what’s going on, they’re welcome to provide another explanation.

If Council — or a majority of them, anyway — believe that this issue is going to die down, they’re sorely mistaken. That referendum result showing an overwhelming number of city voters against the state-imposed gerrymander looms large over this whole issue. Those numbers are also not surprising: opposition to the far-right legislature in Raleigh is one of the few unifying factors in our city’s fractured politics.

Bluntly, Council bowing to a GOP-drawn gerrymander while giving themselves another year in office that the voters didn’t give them is an ugly look. That’s why public pressure is growing.

In the end, they will have to choose whether to fight or flee. Asheville is watching, very closely, to see which path they take.

—

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by our readers. If you like what we do, donate directly to us on Patreon or make a one-time gift to support our work. Questions? Comments? Email us.