Behind the controversies that weren’t discussed, the Airbnb presentation that wasn’t presented and the closed door dilemmas looming over a brief, bizarre Asheville City Council meeting

Above: Asheville City Council. File photo by Max Cooper

As a place where systems of power touch the ground, a local government meeting can be many things. Asheville City Council’s are certainly no exception. Over the years we’ve seen contentious meetings, marathon sessions, public debates, intrigue, policy “sausage making” done live, personal grudges and policy differences all play out in that 1920s-era dais bracketed by racist paintings.

But Feb. 26 was something else. It was a bizarre Council meeting, one defined strangely more by what wasn’t said than what was.

The meeting was, for starters, not just short but positively miniscule. From the opening gavel until Council went into closed session was just over 42 minutes.

Not the briefest Council meeting, certainly, but fairly close. In the past, such short meetings have usually marked lulls in political battles, gaps in debates.

The odd thing was that by the tail end of February Council certainly had plenty to talk about. Unusually, the meeting was bookended by lengthy closed sessions. The first started at 2:30 p.m., well before the beginning of Council’s formal 5 p.m. meeting. The latter kicked off as soon as Council shot through their already fairly short agenda.

That meeting was dedicated to continued discussion of the appointment of the next city attorney, a process that’s been shrouded in mystery and has dragged on longer than city officials anticipated. When the meeting wrapped, Council went back into closed session to discuss an unspecified “lawsuit or potential lawsuit” and a personnel matter (likely, once again, the appointment of the city attorney). The length of these closed door deliberations, and the fact that the city’s had to re-advertise such a high-level position, indicate that there’s either some serious issues on this front or that Council has some serious divisions over who should occupy one of the most powerful jobs in the bureaucracy. None of that, of course, were mentioned in public.

The meeting also took place on a day when Buncombe County Sheriff Quentin Miller announced the office would cease most of its cooperation with ICE. In communities around the state this step has been followed by ICE terrorizing Latinx communities in retaliation. But not even a statement of concern for those residents, nor one of basic support for Miller’s measure, came from any member of Council.

The agenda even contained a report about the enforcement of the city’s restrictions on Airbnb-style rentals. That massively controversial topic is obviously one of public interest in our community, and the report raises some key questions about enforcement of the city’s rules. But the matter wasn’t presented to Council despite the brevity of the agenda. Locals were simply told the report was available online.

Even the major item Council did discuss — adding a new program to its affordable housing arsenal — left out some major details.

So, somewhat unusually for a piece about Council, we’re going to delve into not just what Council discussed, but what they didn’t. Let’s look at what wasn’t said about the policies they passed, the contents of the report that wasn’t presented and the topics looming over our city where silence, once again, proved the order of the day.

The homeownership push

The main item Council discussed during the meeting was an assistance program intended to help cash-strapped locals muster a downpayment on their first home.

This proposal marks an important shift in how Council’s approaching Asheville’s affordable housing crisis. The problem’s certainly not new; it’s been an increasingly harsh reality for well over a decade. But despite the city’s efforts the housing situation considerably worsened during that time. Asheville is now one of the most rapidly gentrifying and unaffordable cities in the country.

The Airbnb rush, which saw landlords who owned multiple properties turn out locals in favor of tourists, threw gasoline on what was already a pretty bad fire.

In 2016 Ashevillians overwhelmingly supported the city taking out $25 million in bond funds for affordable housing. Historically, city government has used its resources to back the construction of rental housing — mostly through non-profit developers — with an assured affordable rental rate for a set period of time. They’ve also offered incentives for private developers to include a percentage of affordable units in new apartment developments. This approach hasn’t been without controversy, including over whether the rates the city sets are actually affordable, and if they drive a hard enough bargain with developers.

It’s also, as even most of Council would admit, insufficient, as the crisis has metastasized over the past decade. So over the past year, Council has emphasized using some of their affordable housing funds to help locals become homeowners, as well as trying to create more units they can rent at a supposedly affordable rate.

The downpayment assistance program (or DPA) is a major part of that. Using $1 million in bond money, the city also secured $400,000 from Federal Home Loan bank to start the new program. That latter amount is intended specifically for downpayment help for police, fire and teachers working for the city who make 80 to 120 percent of the area median income (why their pay rates are such that they can’t comfortably afford a home in town was, naturally, not discussed).

Who would qualify for the DPA? Aside from city workers, the program’s targeted at locals making 80 percent or under of the area median income (that tallies to about $36,000 a year for an individual). Half of the city’s $1 million would be initially reserved for locals making 60 percent or less of the area median income (about $26,000 a year). The home would have to be within city limits, the person receiving the help would have to be a first-time home buyer with at least $1,000 in the bank and go through a home buyer education course. The maximum amount of assistance would range from $25,000 to $40,000, depending on the applicant’s level of income. The loan would only be due if the home was sold.

“This is a way to use the DPA to lower that monthly mortgage payment to an affordable level,” Paul D’Angelo, the city’s housing development specialist, told Council. “We’re excited to get some things moving here for everybody.”

Council members were enthusiastic.

“When we first started talking about this it felt messy, I didn’t see the path to how we’d get there,” Council member Julie Mayfield said to D’Angelo. “You’ve led this ship ably through these really complicated waters.”

She added that she believed the policy would focus on helping those who needed it most, “this is a really big milestone.”

“There’s a chunk here for those that really need it,” Council member Keith Young said, referring to the funds set aside for people making 60 percent or less than the median income.

However, the program’s got a more complicated path than it might seem, and some important restrictions and exceptions that didn’t get their due at the dais. In the days after its passage, members of the public were already asking questions (including from this reporter) wondering if they qualified and if the housing they could find even if they did would actually be affordable. Would student or medical debt hold them back? Indeed, after listening to those queries and poring over the policy in detail, there’s a lot of question still remaining.

For one thing, in addition to the applicant needing $1,000 (almost half of Americans can’t even cover a $400 expense), they have to have no higher a 43 percent debt-to-income ratio. What counts for that debt? How is that ratio calculated? As with a lot of the downpayment assistance program, it turns out it’s up to the individual banker.

“Whatever works with the bank or lender,” D’Angelo tells the Blade when asked about the debt ratios. However, he emphasizes that the point of the program “isn’t to reject people, it’s to help low and moderate-income people get a home.”

There’s more. The applicants are ineligible for the downpayment assistance if they’ve ever been evicted from public housing. That’s important because public housing evictions are a major controversy, with some residents and activists asserting they’re often used arbitrarily. A 2015 investigation of eviction rates in public housing saw officials unable to explain several major spikes. Due to Asheville’s massive segregation in public housing, that ineligibility requirement would overwhelmingly shut out African-American residents, even if they met the income requirements and had money in the bank.

D’Angelo said that prohibition, like a lot of the DPA’s other restrictions and requirements, was formed from a list of “best practices” that emerged from working with the city attorney’s office consulting with multiple banks, agencies, realtors and housing non-profits. He notes that the eviction issue, like some of the program’s other prohibitions, might not outright bar someone from receiving the assistance if city officials and the others working on securing them a home review the circumstances and find they believe “this is a good person, a good family.”

Acknowledging that having $1,000 on hand is an obstacle for many people in the income brackets the policy seeks to aid, D’Angelo adds that the funds don’t have to be available all at once. Locals paying for things like an appraisal or closing costs as the process of buying a home continues would deduct from that amount, he notes.

But there’s more. The median price for a home in Asheville is around $335,000. Assuming a 30-year mortgage at an average rate, they’re looking at over a $1,300 to $1,500 a month payment even if the borrower gets the maximum in downpayment assistance. That would, under the federal government’s criteria, leave most people who receive this assistance still rent-burdened unless they had an incredibly good deal or other resources at hand.

D’Angelo claims the intent is that people using the program will get additional financing through other sources as well, such as organizations like local non-profit Mountain Housing Opportunities and the North Carolina Housing Finance Agency.

Also: rather than going to the city directly (though D’Angelo emphasizes he welcomes questions and will be engaging in public outreach) he generally believes that lenders already working with a local will come to the city “to get that last $20,000 or $30,000 to make this work.”

Of course, even getting to that stage of the process can be a challenge for many locals, and that leaves a lot of the process with this program in the hands of banking institutions. Asheville was hit particularly hard by redlining, which led to black households often being denied home loans. While the practice has been illegal for decades, racial housing discrimination that often prevents black households from getting fair rates remains a problem nationwide. A New York University study of 4 million housing loan applications found that black households were twice as likely as white ones to get subprime mortgages. Indeed, well-off black families making $200,000 or more were more likely to be offered substantially worse terms than a white family making $30,000.

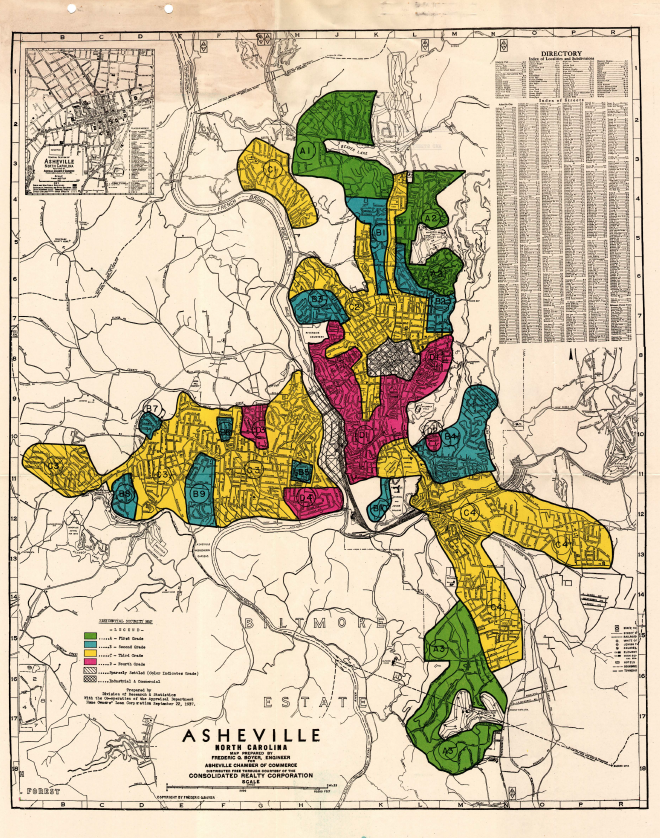

The 1937 HOLC map of Asheville. All but one of the areas marked in red are majority African-American. Practices stemming from redlining still make it far more difficult for black households to get fair home loans.

Asked if the city will monitor the results of the downpayment assistance program to ensure it’s promoting equity, not decreasing it, D’Angelo replies that they’ll follow up every three months on the state of the program in general, but doesn’t specifically note if they’ll monitor which demographics the assistance is going to or if those reports will be directly presented to Council.

None of this is to denounce the program, or to assert Council shouldn’t have passed it. But it reveals some important complexities and limitations that really, really should have been openly discussed at the Feb. 26 meeting. They should definitely be discussed publicly going forward.

The presentation that wasn’t

Typically, in shorter meetings Council will receive presentations on different city programs or boards. Indeed, one was scheduled for the Feb. 26 meeting. Specifically, Council was supposed to get an update on its enforcement of its prohibition on Airbnb-style rentals of whole homes and apartments. You can read the whole report here.

The issue is a major one in Asheville, where Airbnbs take up three percent of the housing stock, the highest rate of any city in the country. Housing advocates have repeatedly asserted that landlords turning so much housing over to tourists basically drastically worsened an already dire housing crisis.

Over the past few years a public backlash grew. In the 2017 elections, the main candidates sympathetic to loosening the city’s restrictions on Airbnbs were badly trounced, failing to even make it past the primary.

Over years of political conflict the city opted for a two-pronged approach. It relaxed restrictions on locals renting out rooms in homes they occupied (a practice called “homestays” in the city’s official rules). But it strengthened restrictions on renting out whole apartments or houses to tourists (“short-term rentals” in city jargon) and then, under public pressure, strengthened them again.

Last year, the ban was extended to cover nearly the entire city, including areas like downtown and the river district where the practice had previously been allowed. Those short-term rentals that got legal approval before last year’s ban (they were always illegal in most of the city) were allowed to continue operation as long as they kept their permits current. According to the city’s report, 180 units fit that bill. The only new Airbnbs are supposed to be homestays or, if a whole housing unit, ones that received direct approval from Council for an exemption to the ban (which this Council hasn’t ever granted).

But passing a law is one thing; enforcing it is quite another. The latest report — the one Council and the public didn’t hear — reveals some interesting numbers on that front. In 2018 the city issued 272 new homestay permits and 394 old homestay permits were renewed, making for a total of 666 homestays (yes, really).

That’s a massive increase in homestay permits and given that 2018 was the year the city passed far tighter restrictions, it’s worth asking if that surge is tied to owners of formerly illegal Airbnbs rushing to get homestay permits. Does each one of those units now have a local resident living there full-time? If so, Council’s action just added 200+ housing units back in the market. If not, the city has a much more serious problem, and the damage the industry’s inflicted on Asheville just continues under another legal cover.

A 2016 Blade investigation of the city’s enforcement of its Airbnb restrictions revealed a relatively lenient attitude, at the time, with landlords routinely given grace periods to continue renting the property to tourists rather than immediately being required to stop. It also showed some cases where homestay permits were being issued even though the landlord had previously been renting out the entire house or apartment to tourists, or where it was unclear any resident lived on the property. Often, rather than collecting and enforcing fines, city staff would encourage the landlord to get a valid homestay permit.

Ostensibly, that’s supposed to mean a local is now living in each of those 666 properties, and that tourists are only staying in a room while the local is there. But previous investigations of the Airbnb industry in this town showed that while some actual homestays certainly existed, overwhelmingly whole units and apartments were the hot commodity. An entire house or apartment is a lot more appealing in a tourist destination and can fetch a much higher price. The city’s report found that they had identified 1179 Airbnb-style rentals, of which they claim over half are now legal homestays.

What about the properties that are violating the city’s rules? Well in 2018 the city didn’t actually find (or fine) that many of them. That whole year saw just 204 enforcement actions. By the time of the report, 68 properties were still out of compliance and just 19 cases. In all of 2018, the city just collected $16,700 in fines (which go to local education systems, not directly to city coffers).

That’s low, considering that Airbnbs alone take up three percent of the city’s housing supply, that the city can levy $500 a day fines for those who break the ban and that a single Airbnb landlord already owes the city over $1 million in fines.

So the report, especially the relatively small amount of fines collected, raises some serious questions. Are city staff going full force after relatively wealthy landlords who are, at this point, blatantly breaking the law? Is the enforcement too lenient? Are homestays being used, in numerous cases, as another cover for continuing to hock out whole units on Airbnb while no resident actually lives in the space? How strictly are city staff monitoring the homestay permits to ensure they don’t just become a giant loophole?

These are all important questions. It would have been great if Council had asked them, and the public had heard the answers. But they didn’t.

Elephants in the room

Outside of the agenda there were even more important matters Council could have considered, but didn’t.

Feb. 26 was, after all, the day Sheriff Miller — after a lot of pressure from local activists and the Latinx community — announced that his office would no longer cooperate with ICE. That means they won’t honor ICE detainers — a request from the notoriously racist agency to hold someone in a local jail they suspect of being undocumented. From now on, Miller asserted, they would only honor far rarer criminal warrants actually signed by a judge. He reiterated that the office would not assist ICE in its raids or sweeps.

ICE has responded to similar declarations by other North Carolina sheriffs by carrying out raids in retaliation. If that happens, they will hurt people within the city as well as the county. Miller’s move also raises questions about how local law enforcement in general — including the Asheville Police Department — deals with immigrant communities, and if the city will declare its support for the sheriff’s declaration. Several Council members have criticized ICE’s actions before.

But whatever feelings about the threat posed by ICE existed on Council they didn’t talk about it. Whatever reassurances the people of the city needed, they weren’t forthcoming. No one mentioned the issue at all, even to personally weigh in or say that further statements or action would be forthcoming.

There’s more. The city has a fight over a $190 million budget looming. Last year, city staff and some on Council kept the budget process notoriously brief, obscured multiple controversial issues and shut out the public (the only public hearing on the issue took place late at night). A public backlash grew. The budget only passed by a single vote, and a local activist was arrested in an act of civil disobedience, protesting the lack of transparency and the budget’s move to expand policing rather than put funds towards social justice efforts, transit and housing.

This year, in the wake of that controversy Council started public budget presentations far earlier. But even new City manager Debra Campbell acknowledged at the beginning of this year that the city’s attempts to get public input have fallen short.

A meeting with this light an agenda would have been an excellent opportunity to at least discuss the upcoming budget process a bit more, or even schedule an opportunity for the public to weigh in with some of their general wishes for the upcoming budget before Council and staff hash it out over the next few months. The topic wasn’t even mentioned.

There’s also the looming question of if Council will fight a state-imposed racist gerrymander of the city’s elections. Public anger on that issue has also grown, as the city’s not fought the new system in court (other N.C. cities have fought similar laws and won). Just over a month before the February meeting, Council claimed they were investigating the issue and getting more information from the city attorney. But nothing about the key issue was said, not even a “we’re still weighing our options.”

Then there was the issue that began and ended Council’s activities that day: the search for the city attorney. The job is one of the most powerful in all of city government, along with city manager. While Council’s process for selecting the latter position had its shortcomings (they reneged, last minute, on a promise to let locals directly hear from and question the city manager candidates) there were at least some opportunities for the public to make their feelings known.

As the Blade revealed late last year, however, no such public input was sought for the city attorney job. The committee advising Council was composed entirely of city staff, a fact officials only admitted after repeated questioning. In January Council revealed that their efforts to find a new attorney had failed, and they would continue the search. They’re searching still.

That leaves two possibilities. The first is that Council was unable to find a candidate for the position due to a lack of applicants. That would be unusual, to put it mildly. A new city attorney would likely make between $160,000 and $200,000 a year and have a job that would give them a major resume boost for their future legal career.

The other possibility is that Council can’t reach any agreement on who should be city attorney. Either no candidate can muster the necessary four votes or Council doesn’t want to have a contentious split vote on a position this important. This wouldn’t exactly be a surprise. Robin Currin, the previous city attorney, was known for far-right legal views on issues from equity to housing to LGBT rights. Some of Council’s more progressive members have faced public pressure on the city’s actions (and lack of action) on those topics during Currin’s tenure, and it’s not hard to see them wanting someone who aligns with their views more this time around.

The length of the closed sessions and the rare fact the city had to re-advertise for a position that lofty certainly indicate that something is up. While Council faces some constraints from personnel laws, they can certainly discuss issues or goals in general terms. At this point it looks like there’s a major political crisis going on behind closed doors. But, again, no one’s talking about it.

The people of Asheville deserve better. None of Council were elected to stay silent. They are, whether they like it or not, public officials crafting public policy and making decisions that impact the public. They need to do a lot more of that decision-making in public.

Given the city’s repeated crises and injustices, silence is not acceptable. Silence in City Hall has cost lives and neighborhoods, it has fostered a culture where the public are seen as an obstacle and a nuisance rather than the people who must, in the end, hold the reins of power. Silence will not break Asheville’s problems because silence created them. If Council won’t speak, the public must.

—

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by our readers. If you like what we do, donate directly to us on Patreon or make a one-time gift to support our work. Questions? Comments? Email us.